January 3, 2020

This is the third installment of a 3-part Nutrition Business Journal series. Read part 1 and part 2.

In 2012, eight natural products industry leaders gathered at Lara Dickinson’s California home to brainstorm. Dickinson, a long-time industry marketing and sales exec, and co-host Ahmed Rahim, CEO of Numi Organic Tea, had dreamed of creating a community of mission-driven, high-powered visionaries to work together to improve the industry and planet.

What the group mapped out around Dickinson’s dining room table became OSC²—One Step Closer to Organic Sustainable Community—an effort to tackle the industry’s and planet’s toughest sustainability problems. But a different kind of problem emerged. “I couldn’t find a single woman CEO to sit in the room with us,” says Dickinson, who co-founded the group with Rahim and serves as its executive director. Many women CEOs don’t have time to think beyond their businesses, she says, although that’s shifting. “It took me two and a half years to get our first woman at the table.”

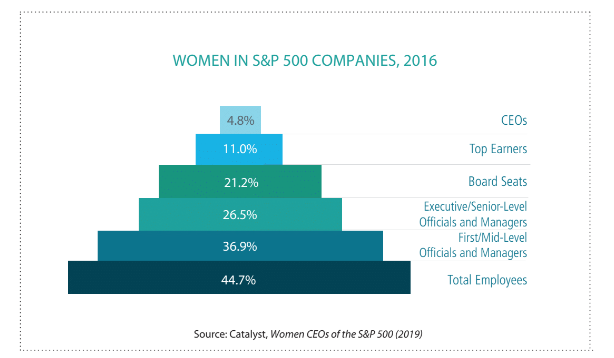

From natural product industry C-suites to board rooms, “there’s a clear lack of women,” Dickinson says. Some natural products companies tout their high percentage of women employees, but the key question is “how many are making vital decisions?” she says. “We can all do better.”

For decades, women have hacked at the glass ceiling, but the problem is growing more urgent. “The empowerment of women and the education of girls globally is the single largest thing we can do to address climate change,” Dickinson says, referring to the role education and employment play population growth, among other things. “It’s all connected, and the line is short.”

“Women are visionaries”

Several studies document an array of bottom-line benefits—including higher profits—for organizations with more women in senior positions. These include greater creativity, productivity and innovation and less discrimination in hiring and promotion.

MegaFood has more women leaders than men, says Bethany Davis, the company’s director of advocacy and government relations. “That has been an amazing experience,” she says. “We are not scared of women here—we are inspired and excited about how powerful they are. Women are visionaries, and women are unflappable. We don’t give up easily.”

Employee engagement, satisfaction and retention also rise when more women are part of the leadership team, studies show. “When I talk about my experience, women are blown away and wonder, ‘How do I get myself a job at a company like that?’” Davis says. “You want to have people clamoring to work for you. One way to do that is to empower women and let them brag about you.”

Prioritizing gender equality also enhances brand reputation and public goodwill, studies show. The highest-ranking organizations on Fortune’s World’s Most Admired Companies list, for example, have twice as many women in senior management as companies with lower rankings.

Still, few women helm America’s top-grossing companies. When Bed, Bath & Beyond named Mary Winston Interim CEO on May 13, the number of women CEOs leading Fortune 500 companies grew to 33, an all-time high. That’s still a disproportionately small part of the whole—only 6.6%—but a jump over 2018, when the number fell to 24 from a record 32 the previous year.

Still, few women helm America’s largest companies.

“A critical mass”

A lone woman CEO or director, however, isn’t likely to make much of an impact. The greatest benefits arise from what researchers call “a critical mass of women”—roughly around 30% or at least three on a corporate board. When more women hold top jobs at a company, all women’s voices are more likely to be heard, group dynamics change, and innovative ideas and better decisions emerge.

When a corporate board includes at least three women, financial performance improves, volatility decreases and investment in R&D rises compared to all-male boards, studies show. Researchers also found less fraud, fewer financial reporting mistakes and greater social responsibility performance among gender-diverse boards.

The Organic and Natural Health Association (O&N) Board recently expanded, electing three women. “It wasn’t intentional that our new nonprofit began with me being the only woman at the table,” says Karen Howard, CEO and Executive Director. “But after four and a half years, the time was right for expansion and the benefits of diversity. I was thrilled, though not surprised, they elected to actively recruit women for three new slots. After all, our work is rooted in consumer interests, 50% of whom are female.”

Beyond benefits to individual organizations, increasing women’s board participation is “an issue of American competitiveness in a global economy,” says The Committee for Economic Development of The Conference Board, the non-profit, non-partisan, business-led public policy organization behind major economic initiatives such as the World Bank and the Marshall Plan.

In the U.S., women held only 24% of S&P 500 board seats in 2018. About a third of those boards included three or more women. Last year, 40% of new directors were women—9% of them women of color, up from 6% the previous year.

California quotas

Under a new California law, publicly traded corporations based in the state must include at least one woman on their boards by the end of the year. The quota increases to at least two women for a five-person board and three women for boards with six or more members by the end of July 2021, and companies that don’t comply can face significant fines. At least seven countries, including France, Germany and India, have established gender quotas for public boards.

While men seem to hold a majority of senior positions in the natural products industry, it’s unclear how many women are in these roles. “Across the natural products industry, there are opportunities for women in leadership positions,” says Heather Granato, vice president of content for Informa (which owns NBJ). “We all need to be setting a high bar and holding each other accountable.”

Granato has worked to raise industry awareness about the bottom-line benefits of women in leadership. For each of the past three years, for example, the SupplySide education schedule, which she oversees, has included a panel touting women in leadership. The sessions focused on boosting ROI, the benefits of conscious leadership and business transformation for a profitable future.

This year, Granato is doing even more. SupplySide West 2019 included a three-hour workshop on how diversity and inclusion are good for business. “Women bring a different perspective to the table,” says Granato, an industry veteran who, for decades, has helped women develop their leadership skills, in and out of the workplace. “From a business perspective, it makes sense to invest in women in leadership.”

Key leadership skills

Research shows that women employ specific leadership skills that pay off for organizations, says Amina Faham, PhD, global associate director, pharma application development & innovation for DuPont Nutrition and Health. “While men and women all apply good leadership behaviors, they do so with different frequency,” says Faham, who presented on the topic at Healthy Ingredients Europe last November in Frankfurt.

Of nine leadership behaviors identified as key to organizational success, men and women equally use two—intellectual stimulation and efficient communication. Men tend to employ two more key behaviors—control and corrective actions and individualistic decision-making—more than women. Women, on the other hand, tend to use five of the nine critical behaviors more than men: people development, expectations and rewards, role modeling, inspiration, and participatory decision-making. “These elements lead to improved financial performance of companies,” Faham says.

Investors are taking notice. As the #MeToo movement ignited a greater global focus on women’s empowerment, so-called “gender lens” investing has taken off. Financial services companies such as Morgan Stanley and Athena Capital Advisors have created guides to help investors find pro-woman companies, and Bloomberg’s Gender-Equity Index is a first-of-its-kind framework to measure public companies’ commitment to women’s equality and advancing women in the workplace.

Yet, for many natural products industry executives, the gender make-up of their leadership team is either not on their radar or seen as irrelevant, says Howard, O&N CEO and executive director. These are people running successful organizations, she adds. “They think, ‘Why change what I’m doing when it’s working well as it is?’” she says. “They are not being disingenuous, and they are not sexist.”

“The best candidate”

Industry veteran Peggy Jackson dismisses suggestions that women might be at a disadvantage in hiring and promotions. A job “should go to the best candidate, period,” she says. “I just don’t feel like we’re being suppressed in that area, so I’m not going to stand on a bandwagon and say, ‘You gave the job to Bob and not Sally.’ It has not been harder for me to move up, but it could be in other companies.”

Jackson, vice president of sales and marketing for IngredientsOnline.com, joined the company in August 2015, shortly after founder and president Sherry Wang took it live. Working at a woman-owned company with a staff that skews female “is exhilarating, for sure,” Jackson says. “The women in leadership that I know, they’re moving and shaking and making it happen. They are very serious about what they do. Those women have earned their positions because of their talent.”

To be clear, no one likes tokenism—least of all employees, who want to be valued for their contributions. Yet one study, which looked at top officers at 1,500 companies from 1991 to 2011, uncovered a “hidden quota effect.” Business professors at Columbia University and the University of Maryland found that when one (and only one) woman was hired for a top position, the chances of a second woman nabbing a top-tier spot in that firm dropped by about 50%. Interestingly, men are likely to view hiring practices as equally fair to men and women once at least 10% of board members are women, another study found.

Diversity experts say biases—including those people themselves aren’t aware of—often determine who gets hired and promoted.

Prejudice against women leaders

Mirror imaging bias is another well-documented roadblock for women and people of color. It’s the idea that because decision-makers consider themselves good and successful employees, they unconsciously assume the same for applicants who are similar to them.

One woman agreed to talk about her frustration with this if her name wasn’t used. “Sue Smith” made a lateral move to become a produce department supervisor at a large natural and organic market that’s part of a multi-state chain because of opportunities for advancement. Instead, she found “a total good ol’ boy network,” and, after more than a year, she says she’s had “no growth, no development, nothing at all.”

Smith, who had extensive management experience in another industry, says she’s made it clear to her team leader—a young man in his early thirties—that she wants to move up and tackle more responsibilities. “I had to constantly ask to get him to teach me anything. He was constantly taking the other two supervisors under his wing and showing them things but telling me there wasn’t training—it was all just learning on the job,” she says.

Smith watched one colleague, a 20-year-old about half her age, advance ahead of her to associate leader, even though he didn’t outperform her. “My team leader told me many times that that young man reminded him of himself,” she says.

Missed opportunities

Smith was featured in two previous NBJ articles about gender discrimination, including talking about the sexual harassment she’s experienced from customers and a co-worker. “That’s gross,” she says, “but what’s really more damaging is when they’re not giving you opportunities.” The situation has only worsened in recent months, she says, “and I’m leaving this industry as a result.”

Such mirror-image hiring is easier for managers in the short term, OSC²’s Dickinson says, but carries a steep price. “When we hire people like us, we miss huge opportunities for innovation,” she says.

Dickinson recently saw this concept in action with her 10-year-old daughter’s Lego robotics team. Although most teams were comprised of a single gender, her daughter joined a co-ed team. “It was harder at first,” Dickinson says. The kids didn’t get along and their first scrimmage was a “massive failure,” she says.

Then some parents stepped in to help the kids understand each other and identify their goals. They won the finals, Dickinson says, “by a landslide.”

Inclusive recruiting, hiring and promotion

Counteracting unconscious bias “is a challenge,” says Granato, the Informa vice president. “You ultimately want the best candidate, the person who’s going to be the best fit for the job,” she says, but that means developing an inclusive recruiting, hiring and promotion program.

For starters, companies may want to review recruitment materials. Job descriptions that included more words associated with male stereotypes—for example, “competitive,” “dominant,” and even “leader”—were perceived to be male-dominated occupations and were less appealing to qualified women, according to a 2011 study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Similarly, if a company has one woman in its finalist pool, there’s statistically no chance she’ll get the job, according to research from the University of Colorado’s Leeds School of Business. This is true even if the finalists have equal experiences and qualifications.

A lack of confidence

While bias, sexism and racism can create serious roadblocks for women in the industry, another obstacle to moving up is even more insidious: women’s own attitudes.

Women dream of moving into C-level jobs at about the same rate as men (79% to 81%, respectively), and they’re almost equally willing to sacrifice part of their personal lives to do so (61% to 64%), DuPont’s Faham notes. Yet, only 58% of women middle managers and 69% of women senior managers said they expected to succeed in reaching their top-management goals, compared to 76% of male middle managers and 86% of male senior managers, she says.

“I’ve seen it through my career,” Faham says. “We have the same ambition as men. We’re willing to make the same sacrifices. The discrepancy really lies in our confidence to succeed in reaching those positions. We need a supportive environment that makes us feel like we can succeed on the job.”

In the global food industry, only 2.7% of women rise from entry level to manager, she says, and only 37% of women say their managers have offered advice to help them advance.

Once senior managers understand the opportunities and challenges of moving women into leadership, there is much they can do, Faham says. DuPont approaches the issue from a variety of fronts, including assembling diverse hiring panels, offering unconscious bias training, and running leadership development and mentoring programs for women.

It takes time

As the benefits of women’s leadership become better recognized, more women will move into those positions, Granato says. “We’re not going to see change overnight,” she says. “It takes time to get people through the pipeline.”

It takes three to five years to see results from diversity programs, says Dupont’s Faham. That’s why “persistence” is one of three game-changers Faham cited in her Healthy Ingredients Europe presentation. The others: full CEO and management commitment and holistic programs that ingrain diversity at all levels.

Faham’s female employees “have the potential to grow, but they’ve never come to me,” she says. “We go to them.” Identifying high-performing women and providing individual feedback helps them gain confidence, she says.

Davis, the MegaFood advocacy director, provides an eye-opening example. She was raised in a religious home, where her father was the breadwinner, and leaders at church and her religious schools were men. “I always saw myself as a partner to someone who had big ideas,” she says. “I thought I could help other people do great stuff.”

“A woman who knows her value”

Robert Craven, MegaFood’s former CEO, and Richard LaFond, vice president of R&D, challenged Davis to lead. “They were the first people to say, ‘You have great ideas and you should be speaking up,’” she says. “It actually took men in positions of power in my company to reflect back to me my potential, for me to see it in myself. I’ve experienced new parts in myself as a woman who knows her value and doesn’t put limits on it. I can see how that affects other women.”

Like Davis, Granato says she’s benefitted from support and encouragement throughout her career. “I’ve had positive role models and mentors who are both men and women,” she says.

In 1998, Granato started at Virgo Publishing, an organization committed to women in leadership. That’s also a top priority at Informa, which bought Virgo in 2014. After last summer’s merger with UBM, one of the first goals for the new Informa Group’s consolidated HR team was to create a three-year plan focused on diversity, inclusion and women in leadership, Granato says. “I’ve been very fortunate to work at good organizations,” she says.

Dickinson, on the other hand, says she’s had no women mentors. “It’s been tough, and I think we all need to learn how to ask,” she says. “‘Am I confident enough to even make these connections?’” Men are more willing. I’ve found this consistently.”

Some women hesitate because they don’t feel secure in their jobs, Dickinson says. “It’s the confident women that will step up and help other women,” she says. “The more we can support and empower women, the more they will empower each other.”

JEDI pilot project

When American women feel empowered, they’re more likely to support the empowerment of women in developing countries, Dickinson says. This is partially what inspired OSC²’s JEDI project—which stands for Justice, Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion—a pilot program underway at five natural product companies.

Along with co-founders Dickinson and Rahim, OSC²’s Core group consists of 21 CEOs and founders, including four women. The most recent addition, Miyoko Schinner, CEO and founder of Miyoko’s Kitchen, which creates vegan cheeses, is the first to graduate from OSC²’s Rising Stars program.

Like the Core program, those in Rising Stars demonstrate strong, high-integrity leadership while working for “true food system change,” Dickinson says. But while Core members must lead companies earning at least $10 million annually, the threshold for Rising Stars is $1 million annually.

Of 11 current Rising Stars, only four are men. “That’s not on purpose,” Dickinson says, but she acknowledges the “cross fertilization” and mentorship that occur among Core members and the Rising Stars can give women leaders in the industry a boost. “We help them, and they really support each other, which is awesome,” she says.

“Bringing women up”

Jackson, the IngredientsOnline.com vice president, says mentoring young women at her company is a major focus. “I spend several hours of my day helping them build themselves up in this industry,” she says. “They’re very excited because they see this is the future for ingredients. They see what strong women can do in this industry.”

Howard says she’d like the industry to do more to mentor and coach women to become leaders. “I think we owe it to each other to have positive, reinforcing programs and messaging for bringing women up through the leadership track,” she says.

Shifting demographics make the task even more urgent. Millennials make up the largest segment of the work force, and they prefer working for diverse companies with inclusive cultures, studies show. Young women expect equal opportunities, Howard says.

“This is really important to the future of the industry,” Howard says. “Women should be able to say, ‘I can do really well in this industry.’ We don’t have that. We’re not there yet.”

About the Author

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)