December 17, 2019

This is the second installment of a 3-part Nutrition Business Journal series. Read part 1 here.

It’s not as if Suzanne Shelton hadn’t seen it before—attractive young women wearing next to nothing, hawking sports nutrition products at a trade show booth. Yet, on this particular day, she says the bikini-clad women ignited “a flash of rage.”

She shot over to the booth to confront the (fully clothed) men there. “I said, ‘I find this really insulting—can’t you sell your products without objectifying half the population?’”

That was about 15 years ago. Since then, the natural products industry, like others, has made strides in hiring and promoting women. While so-called “booth babes” aren’t as ubiquitous, Shelton and other long-time leaders say the industry still has work to do to create a fair and inclusive environment for women.

“I have dealt with a lot of misogyny,” says Shelton, who, as Managing Partner of The Shelton Group, has provided public relations and marketing services for industry clients since 1990. “I think it’s the underlying cause of many of the biggest problems facing our society, along with racism.”

Although the recent #MeToo movement initially focused on sexual harassment and assault in the entertainment industry, it quickly grew to encompass other forms of gender-based discrimination across all sectors. Unfortunately, the natural products industry isn’t immune to such inequities—though many argue that with its mission-driven focus, it should be working harder to eliminate the problems.

Gender pay gap

Women earning less than men for the same work is a global problem in the natural products industry, says Amina Faham, Ph.D., global associate director for Pharma Application Development & Innovation at Dupont Nutrition and Health. “This is not ‘us vs. them,’” says Faham, who gave a presentation on tackling the gender pay gap at Healthy Ingredients Europe (HiE) in Frankfurt last November. “It’s an old and illegal issue.”

When wage discrimination is corrected, and women earn an equal amount, the benefits extend far beyond themselves and their families, Faham says. With women making 93% of food purchases, for example, “we can impact any social economy,” she says. “It has a huge impact on the growth of GDP in any country.”

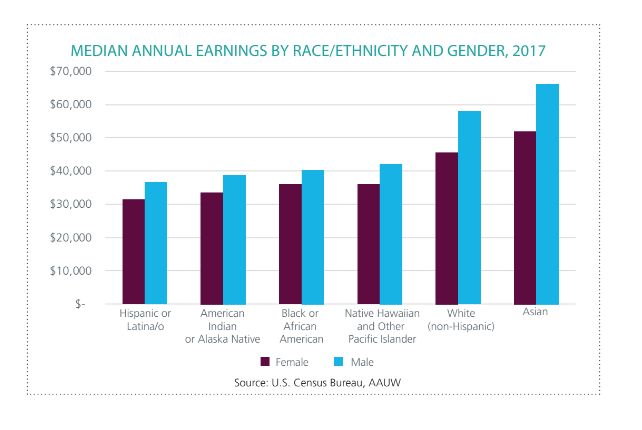

Currently, however, U.S. women in manufacturing, which includes the food and beverage industry, earn 20% less on average than male colleagues performing the same work, Faham says. (This is similar to pay discrepancies across other U.S. industries, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.) Women in manufacturing experience a 22% pay gap globally, Faham says, and a 16% gap in the European Union.

“We don’t talk about it. It’s like a taboo,” says Faham, who’s based in Switzerland. “If we don’t talk about it, there’s very little chance anything will change.”

Heather Granato, Informa vice president of content, hopes to survey industry stakeholders this year about pay, among other issues. Because so many natural products companies are privately held, she says, “it’s tough to find those statistics.”

Pay transparency is one of four strategies Faham recommends to help companies close the gender pay gap. Others include encouraging women mentorship, passing wage equality legislation and building diversity into processes, company culture and core values.

The biggest potential

Make no mistake, creating a workplace where all employees—including women, racial minorities and other marginalized people—feel valued isn’t a call for tokenism or “political correctness.” It’s about organizations drawing from the widest talent pool, helping employees reach their potential and reaping the many, research-proven benefits of workplace diversity, says Lara Dickinson, co-founder and executive director of OSC2, a group of CEOs working to rectify the industry’s and planet’s toughest sustainability problems.

“The biggest potential for our industry is to bring in more diversity,” Dickinson says. “Monoculture does not produce good results long-term—in land or a culture of people.”

Along with regenerative agriculture, OSC2 promotes regenerative leadership, “which means bringing consciousness into your leadership,” Dickinson says. “Being responsible and listening and creating a very inclusive and welcoming workplace is the greatest way to change.”

The more included employees feel, the more innovative they are on the job, and the more willing they are to go “above and beyond” to help team members and achieve company goals, according to Catalyst, a 57-year-old global nonprofit helping businesses work for women.

To do that, organizations must look not only at objective criteria, such as wage discrimination, but also at fuzzier, harder-to-pin-down aspects of workplace culture. In other words, the vibe of the place. For example, are women heard and taken seriously at meetings? (Are they at those meetings?) “There just seems to be this automatic trust in men, and women have to earn it somehow,” says one woman, a natural products industry leader. “It’s true across industries.”

“A woman in produce?”

While many women in the natural products industry say they feel supported at work, not all are so lucky. One agreed to talk about her experiences of working at a large, natural and organic market if her name wasn’t used. In NBJ’s recent Dark Issue IV, “Sue Smith” described sexual harassment she experienced on the job—but that’s not the only discrimination she’s faced. When Smith started at the market, part of a multi-state chain, she was the only woman in the produce department.

“I kept getting the question, ‘A woman in produce?’ and I was a supervisor,” she says. “Instead of calling me by my name, people were calling me ‘Ma’am.’” It stopped only after she insisted that her employees use her name. “It was a very weird, obviously male-dominated environment.”

In every interaction she’s had with her regional manager, “he has called out my gender,” Smith says. “I wanted to leave a while ago because of the sexism in this environment.”

Another industry professional shared her experiences on the condition that her real name not be used. “Jill Jones,” an industry veteran, was five months pregnant in the mid-1990s when she ran into a colleague at an industry event and mentioned her interest in a job that had recently opened at the company where he was a top executive. She was “extremely qualified,” she says, because she’d previously held the job at a sister company.

“He just looked at me—I think he was a father at the time—and he said, ‘Why don’t you have your baby and see how you feel then?’” Jones says. “I didn’t even get to take it to another level of conversation. I knew that was just wrong, but I didn’t know what to do. I was just so angry, I felt like punching him in the nose.”

Since 1978, the federal Pregnancy Discrimination Act forbids discrimination based on pregnancy or childbirth, including hiring, firing, promotions and job assignments. But within a year Jones faced a second, similar situation.

“It affected my life.”

She interviewed for a position she’d held before, with a man with whom she’d co-founded a business. “He knew my capabilities and my capacities,” Jones says. “At the end of my interview (he) said to me, ‘There’s a frequent amount of travel in the job. I know you just had a baby, how is that going to feel for you, all the travel?’ I said, ‘Well, that would be challenging, but I’ll manage.’”

Jones, who has made many hiring decisions, says the question was inappropriate. “Would you ask a man that?” she says. “He had a baby and a wife staying at home. I really felt like I was being discriminated against because of the phase of life I was in. I felt like it was wrong but I didn’t feel I had a recourse.”

She considered filing a discrimination claim. “I didn’t feel emboldened to do it. These were people I liked and respected,” she says. “I don’t like to play the victim, but it affected my life.”

Jones says she still thinks about talking to the men about it. “They are good people. I want to give them some grace because I realize, intellectually, they’re a product of our culture and the times,” she says. “At the same time, they probably don’t remember it. I don’t think they realize their own behavior.”

Many men in the industry aren’t aware of the ubiquitous sexism women encounter—or that they may be part of the problem, says Shelton, the PR exec. “Because men don’t experience what women do, they don’t even realize it’s a thing,” she says. “Part of it is education, and part of it is realizing that you don’t know what you don’t know.”

Shelton recalls one group that used to meet at trade shows to hash out industry problems. “It was always these old, affluent white guys. They would never, ever include women,” she says. “We would laugh at them.”

Bro territory and ‘sex-po’s

Cronyism at industry events has left some women feeling alienated and excluded. An after-hours gathering can veer into “bro-culture” territory, with heavy drinking and unabashed sexist attitudes on display. Natural Products Expo West gets referred to as “Sex-Po.” More than one woman admits to playing down her looks and carefully selecting her wardrobe to avoid unwanted attention.

“I’ve heard comments that would make ‘Mad Men’s’ Roger Sterling pale,” Karen Howard, CEO and Executive Director of the Organic and Natural Health Association, wrote in NBJ’s first Market Overview Issue three years ago. “No one believes words can hurt? They hurt the whole industry.”

But the climate may be shifting, Howard says. “I was just in Anaheim for Expo,” she says. “I didn’t hear one comment or joke that made me cringe.”

That doesn’t mean everyone is on the same page. One popular move for some men is passing off demeaning comments as jokes. Shelton, for example, says one industry leader glibly dismissed her whenever she disagreed with him. “He’d say, ‘You’re so cute. Why aren’t you married?’” she says. “It happened multiple times.”

Bethany Davis, Director of Advocacy and Government Relations at MegaFood, was preparing to debate the use of GMOs at a conference when her opponent—a man in his 60s, about twice her age—approached. “He said, ‘This is who’s debating me? What could you possibly know at your age? Don’t worry. I won’t call you an ignorant slut on stage,’” Davis says.

“No one said anything.”

She didn’t know he was referring to an old Saturday Night Live skit. “It was, literally, within 60 seconds of going up on stage. I was pretty shaken,” Davis says. “He didn’t pay attention to anything I said. He just stuck to his talking points.”

Before the debate, Davis says she’d been standing with other men—“high-integrity men.” Later, they told her they thought the other man’s comments were inappropriate, Davis says. “In the moment,” she says, “no one said anything.”

That’s part of what makes discussing these issues so tricky, women say. Good guys make mistakes. “It’s not about shaming or blaming,” says OSC2’s Dickinson. “We all have unconscious bias and a lot to learn to lead and work together better.”

Dickinson and Sheryl O’Loughlin, CEO of REBBL herbal beverages, have launched the JEDI project, which stands for Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. It’s an internal OSC2 pilot program to increase all kinds of diversity in the workplace, along with ensuring an inclusive culture. They plan to eventually bring the program to the industry, Dickinson says. “White men have been very responsive to the JEDI idea,” Dickinson says. “They get the opportunity to recruit the best talent and to innovate.”

Men are becoming more aware of these issues, women say. Dupont’s Faham, who has spoken about the gender pay gap at other conferences, says she was pleased at HiE to see, for the first time, so many men in the room—making up about one-third to more than half of the audience at times. She also noted many young women.

Young workers will "change our culture”

Those young workers are critical to the industry’s future, especially in a competitive hiring environment, Howard says. Millennials, who now make up the largest segment of the labor force, favor mission-driven organizations that value employee differences—and they expect equal opportunities, studies show.

“They’re going to help change our culture,” Howard says. “They’re going to call people on the carpet about these things.”

While the natural products industry has long prided itself on innovation and trend-setting, organizations that ignore gender diversity may soon be seen as out-of-step and lagging behind. In 2017, more than 150 CEOs from some of the world’s top companies announced the formation of CEO Action for Diversity & Inclusion, a massive effort to improve diversity and inclusion in the workplace. Now, nearly 600 CEOs and presidents, academic institutions and nonprofits have signed on.

The campaign holds that a company’s employees should reflect the increasingly diverse U.S. population—as well as its customers. With women comprising about half of the population and making the majority of food-shopping and health care decisions for their families, this is especially relevant for the natural products industry.

“They’re the ones buying our products,” Dickinson says. “They need to be at the table.”

Howard agrees. “Men should not be making all of these decisions for the female customers we rely on so much,” she says.

In her NBJ piece three years ago, Howard called for the industry to lead on gender equity. “If you aren’t embracing the talents of women into your workforce, you may not be reaching the health advocates you seek to serve,” she wrote. “I encourage urgency in your effort to do so.”

About the Author

You May Also Like