Newtopia Now: Dan Buettner explains why Blue Zones matter

Dan Buettner, a National Geographic Fellow and Netflix host, will share in his keynote address how public-private partnerships can support community health. Learn more.

September 4, 2024

At a Glance

- Dan Buettner discovered specific locations where people are more likely to live to 100—or beyond.

- The people who live long lives in these areas share nine common lifestyle habits, including having strong social networks.

- Blue Zone Project employs private-public partnerships to make healthy choices easier in participating communities.

Dan Buettner likes to solve problems.

Like many journalists who take a solutions-oriented approach, his exploration as a longevity researcher and bestselling author has led to groundbreaking work and the founding of Blue Zones, an organization focused on helping Americans and others live longer, healthier lives.

At the moment, Buettner is between flights, fresh off a trip to the 2024 Aspen Ideas Festival. Listening to a talk by John Kerry — former special presidential envoy on climate under President Joseph Biden and President Barak Obama’s second U.S. secretary of state—just emphasized what is at stake.

“He talked about the $38 trillion problem we have with climate change looming,” Buettner says. “It’s a scientific reality. It doesn’t matter what politics you are.”

“The No. 1 thing people can do, as individuals, is shift their diet away from a meat-based diet to a plant-based diet,” Buettner continued. “The way we eat accounts for about a third of our carbon footprint.”

He hopes someday Blue Zones—places in the world where many people live long lives, sometimes to 100 years—will converge with Green Zones, sustainable spots where local governments, usually through public-private partnerships, promote healthy living in an environmentally-friendly manner. The intersection and convergence of the two matters a lot when it comes to creating healthier outcomes, he says.

“Trying to change our behavior fails for almost all people, almost all the time,” Buettner says. Diets fail. People stop exercise programs or taking supplements, Buettner says, unless the healthy choice becomes the easy choice.

“When it comes to longevity, there’s no short-term fix,” Buettner says. “You have to do the right things, avoid the wrong things almost every day for decades for most of our lives. That’s only achieved by shaping your environment. So that your unconscious decisions are better on a day-to-day, moment-to-moment basis.”

Buettner, a National Geographic Fellow and Emmy-Award winning host and co-producer of the Netflix docuseries, “Live to 100: Secrets of the Blue Zones,” will share his latest ideas in an exclusive keynote at New Hope Network’s Newtopia Now trade show at 12:30-1:30 p.m. on Aug. 27 in Denver, Colorado.

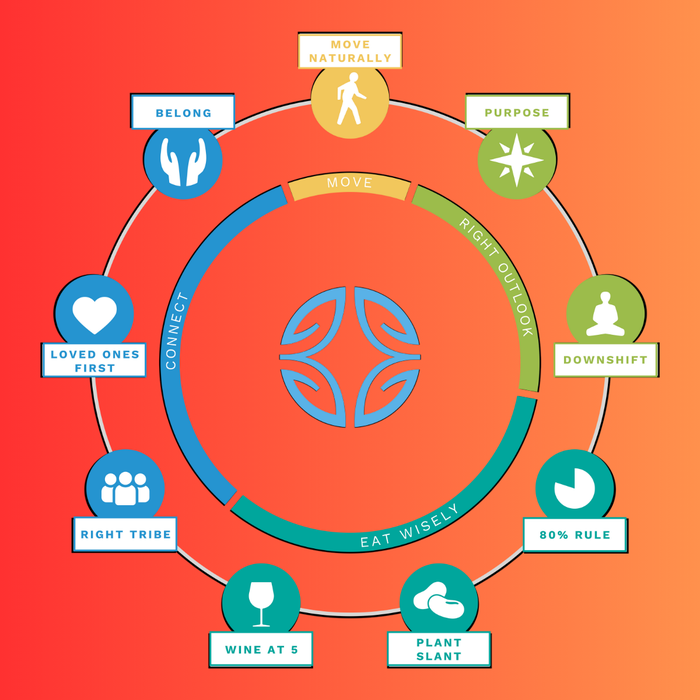

Blue Zones, geographic spots where many people live to 100, shared nine common lifestyle habits known as the “Power 9.” Source: Blue Zones

How the search for longevity began

Buettner’s exploratory journey into longevity took off in 2004 after he received a grant from the National Institute on Aging and National Geographic. He hired demographers, anthropologists, medical researchers and epidemiologists to find statistically relevant places where people live the longest.

Buettner then parsed out the factors that explained longevity. What ensued has become his legacy.

After writing a National Geographic cover story, "Secrets of Living Longer" in 2005 and "The Search for Happiness" in 2017, Buettner hit international fame. Ultimately, he found that Blue Zones, geographic spots where many people live to 100 shared nine common lifestyle habits known as the “Power 9.”

“Happiness and longevity all converge on having a quality social network,” Buettner says. “The best possible thing you can do to add good years to your life is make a cluster of two or three healthy friends with whom you interact with regularly.”

The original five Blue Zones—longevity hot spots with high proportions of people who reached age 100—included the Barbagia region of Sardinia; Ikaria, Greece; the Nicoya Peninsula in Costa Rica; Seventh Day Adventists centered around Loma Linda, California; and Okinawa, Japan.

With the introduction of the Western diet, Buettner says, Okinawa has high rates of obesity and diabetes and, as of 2020, is no longer considered a Blue Zone.

“While the original Blue Zones are being destroyed by the standard American diets and mechanized conveniences, I began looking for new Blue Zones,” Buettner says. “Since I started, there's a new way to measure longevity that actually measures number of years you can expect to live in full health.”

He’s now working on a new project.

“I found areas around the world where people are enjoying an extra dozen years of healthy life expectancy,” he says. “I'm really kind of obsessed with that right now and doing research on it.”

Buettner founded Blue Zones Kitchen, plant-based frozen meals, to help consumers eat healthy meals. Credit: Blue Zones Kitchen

Launching Blue Zones Kitchen

That’s not the only thing Buettner is obsessed with these days.

Approximately 74% of adults in the U.S. are overweight, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Many of the problems come from eating processed foods, sugars and red meats, compounded within a healthcare system that expects doctors to talk to people in 15-minute appointments, Buettner says.

“It’s a problem that has incubated over the past 75 years,” Buettner says. “It's similarly going to take a long time to unwind it. It's not by waving your fingers at individuals and telling them they're bad people. They don't eat healthy. The answer is reversing the toxicity of the food environment we all live in right now.”

Still, there is a happy coincidence, Buettner says. “The foods that make up the diets of the world’s longest-lived people are the cheapest ingredients,” he says. “They’re whole grains, beans and tubers [root vegetables].”

That idea coincided with the launch of Blue Zones Kitchen and its four plant-based, non-GMO, ready-to-heat SKUs. In less than a year, 1,000 grocery stores including Whole Foods Market, Wegmans Food Market and Town and Country Market carry products from the frozen meal line.

To make it taste good, Buettner spent a year working with Abigail Coleman, the former CEO of Territory Foods, who previously worked at a few startups and Kraft, Mondelēz International and Amazon.

“I told her I want a ‘maniacal focus on deliciousness,’” Buettner says.

After dismissing a slew of options, Buettner finally settled on four products—Burrito Bowl, Sesame Ginger Bowl, Minestrone Casserole and Heirloom Rice Bowl which recently won a 2024 People magazine Food Award for Best Vegan Meal. Three SKUs topped Nielsen�’s top three sales receipts for plant-based offerings, Buettner says.

“This proves that food producers can make truly healthy food and make money at it,” Buettner says. “It just involves shifting from following the trends have been for forever.”

Dan Buettner, right, talks and eats with a man while researching Blue Zones. Credit: David McLain

Blue Zones projects continue

Creating better access to healthier options is part of Buettner’s bigger plan to change the trajectory of health and longevity in the U.S.

In 2009, Buettner’s company, Blue Zones, launched its Blue Zones Project with healthy challenges in cities across the U.S.—with an inaugural project in Albert Lea, Minnesota. Through private-public partnerships, cities take a community-wide approach to improve street and park designs, bike lanes and walking paths, as well as change public policy and social involvement.

“Our main job was changing the environments and cities so that the healthy choice was the easy choice,” Buettner says.

The projects require a comprehensive, population-wide intervention involving government policies, restaurants, schools, workplaces, churches, grocery stores and individual homes. Cities working a Blue Zone project are offered a Blue Zone grocery store certification.

“We worked with Cornell Food Labs to come up with evidence-based ways that we can nudge a shopper towards healthier purchases while still maintaining profit margins for grocery stores,” Buettner says.

One of the best ways is with produce, he says, because it has one of the highest profit margins and grocers are interested in “churning that quickly” because of its short shelf life. Displaying fresh fruit, dried fruit and nuts near the front entrance of the store is just one example.

Another thing that’s worked is creating healthy checkout lanes at grocery stores where sugar-sweetened beverages are eliminated from coolers, replaced with bottled water and non-sugary options.

“The profit margins on those things are just as good,” Buettner says. “We put oranges and apples, instead of a Snickers bar because a lot of people don't want to be confronted with that temptation.”

Blue Zones Projects have launched in nearly 80 communities since the program began 15 years ago. “But actively right now it’s just a handful because, during COVID we had to shut down completely,” Buettner says. “These projects are face-to-face. We go out into the community and we couldn’t do that for two years. It takes a while to ramp back up.”

The project has been successful in many places. A Gallup-Healthways study, published by the National Institutes of Health, found a 14% drop in obesity and a 30% drop in smoking among people in a Los Angeles, Caifornia-area Blue Zones Project.

Still, there have been naysayers to Buettner’s work. Most notably, Saul Justin Newman, a post-doctorate research fellow loosely affiliated with Oxford University, who has tried to debunk the Blue Zones as “longevity myth” in a non-peer-reviewed post.

Buettner, who has publicly refuted Newman’s claims, says, “He’s a sociologist who has never been to a Blue Zone. He doesn’t understand demography. His goal is to try and debunk Blue Zones, but he has no qualifications to do so and he’s made tangential claims.”

Citing peer-reviewed journals, Buettner says he’s worked with “some of the world’s best demographers and researchers to identify validated regions where people live the longest.”

Still, Buettner is optimistic. “We tend to seek silver bullets to solve our health problems,” he says. Instead, he thinks about silver buckshot. “It’s being willing to fail on some things and not feel bad about it. In any given city, we unleash 80 or so nudges and defaults knowing that some of these are going to succeed spectacularly and others are going to fail.”

Even if only half of Blue Zones’ interventions work—BMI goes down, life expectancy increases and people report higher levels of happiness—there is success, he says.

“The hardest thing was learning how to scale,” he says. “I learned that you don’t undertake one of these projects unless you have both private and public sectors supporting you and they are willing to sign up for five years. Because this is not fast work.”

Dan Buettner is scheduled to speak at Newtopia Now, New Hope Network's new trade show, at 12:30 p.m. Tuesday, Aug. 27, on the Thrive Stage. Newtopia Now runs Aug. 25-28 at the Colorado Convention Center in Denver, Colorado. Visit the website for more information and to register.

Read more about:

Future of FoodAbout the Author

You May Also Like