Campaign explores true cost of organic v. conventional food

In Europe, the True Cost of Food Initiative is measuring the sustainability performance of different foods to create a more level playing field for the discussion around the price of organic food.

March 15, 2016

Volkert Engelsman has been a busy man. The CEO and founder of Nature & More and Eosta, a Netherlands-based international distributor of organic produce, led the Save Our Soils campaign last year that raised awareness about the dangers of worldwide soil degradation. Now, he’s bringing attention to the environmental and social costs of food production—the externalized costs resulting from agricultural pollution and soil degradation, for example, that our current pricing systems do not account for, and that Engelsman’s latest initiative says amount to $4.8 trillion globally every year.

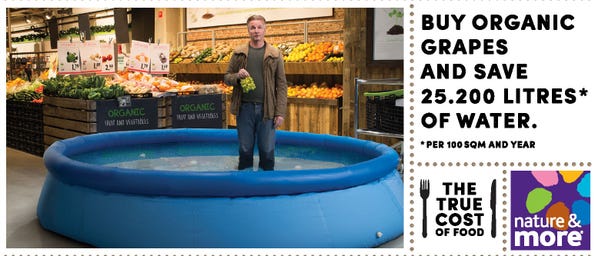

Launched in January, the True Cost of Food initiative aims to teach consumers that if food products reflected their true costs, organic would be much cheaper than conventional food.

Tell us why you launched this campaign, and what your goals are.

Volkert Engelsman: Generally, the public in Europe and America consider organic as too expensive. Equally, they would say organic is not too expensive—conventional is too cheap. It's just that a lot of environmental and social damage costs are not factored into the price. We want to achieve a more level playing field for the market.

In a think tank together with FAO [the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization] and a series of universities, we developed a template to not only measure sustainability performance—with indicators such as soil fertility, biodiversity, climate change, animal welfare—but also monetize it. We communicate to the consumer what the benefit of organic agriculture is on a per-product basis, and we measure the conventional equivalent.

Most of the time, organic delivers a contribution to the environment and to social wealth, whereas conventional exploits labor, depletes soils and emits greenhouse gases. If you are able to monetize that and you publish these values, you get the balance between organic and conventional. This instrument that we launched at the Green Week in Berlin is able to do that on a per-product basis.

How do you see this campaign achieving that more level playing field, exactly?

VE: It will help increase or boost demand for organic products; that demand is increasing exponentially anyway, but it never goes fast enough. Secondly, it will trigger a discussion, whereby conventional suppliers will be challenged to reveal the true costs of their production.

Prices that consumers pay for products won't actually change—so the goal of displaying the "true costs" is to give consumers more context for what's behind the price tags?

VE: It makes it easier for a consumer to pay a little bit more for an organic product, once he knows the societal benefits. As a citizen, he often supports NGOs that look after the environment—but as a consumer, he is often kept in the dark. Now, he is empowered to make an informed purchase decision.

What response have you gotten, and has there been any negative reaction from retailers?

VE: They're remarkably silent. Because it's not us who are communicating these values. It's the FAO of the United Nations.

Retailers are very keen to line up. The greener the retailer, the more keen they are. Customers have responded very enthusiastically and so has the press. We launched it with a retailer in Germany, but we have requests from retailers all over Europe.

What do the communication materials look like in-store?

VE: The ways of communication vary from labels with the true cost analysis on nine performance indicators. Some retailers use posters, others use shelf stoppers. You look at, for instance, apples and see what the environmental footprint is in Euros per hectare, or per kilo, and it helps consumers to make an informed purchase decision.

Do you have plans to expand into the U.S. at all?

VE: We are selling a few products to Whole Foods in the U.S. (mostly bell peppers and tomatoes, but we don't publish the true cost), but we are basically a European company and would love to team up with partners in America who would like to do the same.

Do you have any concern that this kind of campaign could exacerbate the elitist perception that many people already have around organic foods?

VE: Change has never come from a following majority; change has always come from a trendsetting minority. In the U.S., I think you call it the cultural creators or the early adopters or whatever you want to call them.

If you analyze the statistics, the vast majority of people buying organic are not wealthy people. It's not an economic elite; it's an awareness elite. It's a profile of a customer that is usually educated, with an academic degree but not necessarily rich. Obviously there are those who have a higher degree and spending power. So we are targeting the awareness elite, which we consider a multiplier to ultimately come to a more level playing field—so that those who have lower incomes can eventually also buy organic food. In the beginning, it will be difficult to reach out to these people, but you need to start somewhere.

Who's paying for the assessment?

VE: We have a little bit of funding for this from NGOs. But most of the assessment costs are carried by ourselves, Nature & More. It's quite costly, but somebody has to do it. For our own product range, we will not abandon this. We believe there's no sustainability without this kind of cost transparency.

What products have you tackled so far?

VE: It's a series of exotic products like mangoes, pineapples, bananas, and then apples, pears, grapes and citrus. We happen to be a fruit importer, and fruit growers, and we happen to specialize in tropical fruits and fruits from the southern hemisphere. So that's where we started, but we will obviously roll it out to the rest of our product range, and we're teaming up with people to also roll it out to the dairy and meat business.

And this all started from a campaign focused on soil—is that right?

VE: It's true. Last year was the international year of soils, declared by the UN. We teamed up with 200 NGOs to put soil fertility on the agenda. We believe, strongly believe, that that's where it starts. Good soils provide better water-holding capacity, they contribute to biodiversity, they sequester CO2 in organic matter, and they usually provide a way for growers to capitalize on their own soils, rather than capitalizing the input suppliers—regardless of conventional or organic.

So we believe in empowering growers, and we believe that externalization of costs—particularly the costs of soil depletion—should be addressed.

We have been working on this subject for awhile now, and we believe that this is the moment. The Save Our Soils campaign gave us nice momentum, we decided to use the momentum to also start talking about the true cost of food.

About the Author

You May Also Like