FDA’s Modernization of Cosmetics Regulation Act designed to improve safetyFDA’s Modernization of Cosmetics Regulation Act designed to improve safety

For the first time, the FDA is requiring companies to report adverse reactions associated with consumers' use of cosmetics. Learn more about this and other changes.

November 11, 2024

At a Glance

- Under MoCRA, cosmetics companies are required to provide contact information so consumers can report adverse reactions.

- Manufacturers must register their facilities, follow Good Manufacturing Practices and provide evidence of product safety.

- Serious rashes, burns, hair loss and other adverse events are now on the list of adverse events that must be reported.

Most Americans use cosmetics every day. For nearly a century, the laws governing the industry in the U.S. have stayed the same. That’s significantly changing with the Modernization of Cosmetics Regulation Act of 2022, also known as MoCRA.

For the first time in its history, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is requiring companies to report customers’ adverse reactions associated with the use of a cosmetic product. In addition, manufacturers must change labels on hundreds of popular items—by the end of this year—to include contact information for consumers to report those reactions.

It’s the most substantial update and expansion of regulation of the cosmetics industry since the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act was instituted in 1938.

“This is the first overhaul in 86 years,” says Jaclyn Bellomo, senior director of cosmetic science and regulatory affairs at Registrar Corp, a company that helps other businesses navigate regulatory compliance. “Cosmetics have really kind of been left to the side in terms of regulation.”

The new regulations require the “Responsible Person”—the FDA’s official designation of the manufacturer, packer or distributor of a cosmetic product whose name appears on the label of the cosmetic product—to manage and report with more transparency. Companies must manage and maintain adverse event recordkeeping and reporting, implement facility registration and product listing, adhere to Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs), safety substantiation, fragrance allergen labeling, facility suspension, records access and use mandatory recall authority when necessary.

Much of MoCRA centers around transparency in the supply chain.

Bellomo says regulators want to know: Where are products coming from? Where are they made? Who is responsible and what is the safety and efficacy of these products? What type of testing was done? What type of warnings were put on the label and if there is a problem, who can be contacted?

“It puts all those missing pieces together so that a person who uses a product and has a reaction knows where to go,” Bellomo says. “And the person that is responsible for that product can take the next steps to make sure the problem is resolved.”

Starting Dec. 29, cosmetic product labels must include the contact information of the Responsible Person and list a domestic address, phone number or electronic contact information such as a website.

“There’s a huge focus on transparency to ensure the safety of cosmetic products,” Bellomo says. “Industry has tried to push for the last 15 years for more stringent regulations.”

Flood of new brands, state regulations prompted changes

Trying to change the cosmetic industry hasn’t been easy.

“Cosmetics is a $500 billion market in the U.S. alone,” Bellomo says. “It’s hard to put a pulse check on an industry that is that big.” Most products launched in the United States come from independent brands. “With TikTokers, influencers and those dreaming of becoming the next top thing. That’s played a huge part. We’re flooded with brands and products.”

Bellomo says MoCRA addresses “the first step,” of how to control the millions of products coming into the U.S., to start mitigating potential risk at a federal level that’s already being regulated by various states.

States such as California via its California Safe Cosmetics Program; Vermont, which has banned several chemicals including polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAs); and the state of Washington with its Toxic-Free Cosmetics Act, have started regulating cosmetic products.

“I think that really pushed everyone forward,” Bellomo says.

It’s not clear, though, how companies should test their products.

“It’s not like the FDA gave a list of the testing you need to do,” Bellomo says. “Basically, the FDA has left it in the hands of the brands to determine the products’ proper safety testing it has to undergo.” That’s made testing cosmetics more complicated because companies don’t know how much testing is enough.

“People are over-testing their products. They’re going through micro testing. They’re going through compatibility, stability and doing toxicological studies and heavy metal testing,” she says. Her advice: Be thoughtful about what is in your product, its intended use and potential misuse. Businesses must have evidence that proves their products have been tested and are safe to use. It’s important to maintain detailed records.

“Companies will now need to identify the ingredients used in their products and to do proper testing to ensure those products, those ingredients in the product are safe to use and its intended use,” Bellomo says.

What’s required of manufacturers and processors

Cosmetics manufacturers and processors must register their facilities with the FDA and renew their registration every two years.

According to the FDA, a “Responsible Person,” like a manufacturer, packer or distributor, must list each marketed cosmetic product with the FDA. A list of product ingredients must be provided and updated annually. The FDA’s enforcement of facility registration and cosmetic product listings went into effect on July 1.

Brands that manufacture cosmetics outside of the U.S. need a U.S. agent who will communicate with the foreign facility if needed and act as a point of contact in case of product or registration questions or violation. That’s already happening in other sectors, but will now be required for cosmetics.

Certain small businesses—those with average gross annual sales less than $1 million over the three previous years—are often exempt from facility registration and product listing requirements. Products that come into contact with the mucus membrane of the eye, are injected, are intended for internal use or alter appearance for more than 24 hours are not exempt from the registration and listing demands, though.

Exempt small businesses still need to do safety substantiation, adverse event management and labeling requirements, Bellomo says.

Cosmetic manufacturers and processors will need to comply with Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs). What the final rule will look like remains to be seen. The FDA issued draft guidance in 2023. Regulators are expected to issue a notice of proposed rulemaking by Dec. 29, with a final rule to be issued a year later.

Watch the FDA video: Modernization of Cosmetics Regulation Act of 2022 – Key Terms and Provisions

Adverse event definition expanded

With MoCRA, the FDA changed its serious adverse event definition to include cosmetics because some people are dying or having birth defects, Bellomo says. This new part of the law reflects the worst cases they’ve seen in cosmetics.

“Before it was death, inpatient, hospitalization, life threatening and birth defects,” Bellomo says. “Now they’ve added for cosmetics, serious and persistent rashes, second- and third-degree burns.” A serious adverse event also includes anything that causes significant disfigurement, including hair loss, as well as persistent or significant alteration of appearance, or something that requires, based on reasonable medical judgment, a medical or surgical intervention.

If something happens, the FDA requires the “Responsible Person” to submit a serious adverse event report within 15 business days of receiving information about the event via its MedWatch Form 3500A. The seven-page form needs to include details about the individual, the serious adverse event and the suspected product.

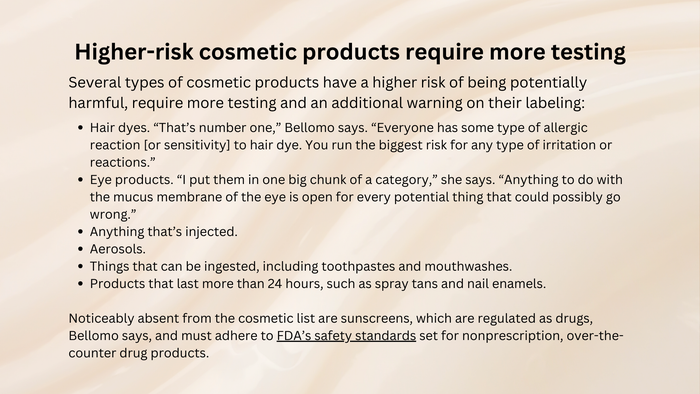

Higher-risk cosmetic products that require more testing

Bellomo says several types of cosmetic products have a higher risk of being potentially harmful, require more testing and an additional warning on their labeling:

Hair dyes. “That’s number one,” Bellomo says. “Everyone has some type of allergic reaction [or sensitivity] to hair dye. You run the biggest risk for any type of irritation or reactions.”

Eye products. “I put them in one big chunk of a category,” she says. “Anything to do with the mucus membrane of the eye is open for every potential thing that could possibly go wrong.” Plus, when you can’t see, it’s the worst thing that could possibly happen, she says, or if you have irritation.

Anything that’s injected. “Tattoo inks are considered cosmetic,” Bellomo says. “Very high risk, in my opinion, of what could potentially go wrong because you're injecting tattooing, there's a potential for infections, cross-contamination. It’s always a little bit risky to put anything into your body through a needle.”

Aerosols are also risky. “Because when people don’t read directions, people spray where they’re not supposed to spray them,” she says.

Things that can be ingested. Anything for internal use can be problematic, Bellomo says. That includes toothpastes and mouthwashes that need to be mindfully used and not ingested in too large of quantity.

Products that last more than 24 hours. That includes spray tans and nail enamels. “All the things that stay on for longer than 24 hours,” Bellomo says. “They run a very, very high risk, in my opinion.”

Anything you can wipe off at the end of the day is okay, she says, but if it’s a spray tan that lasts for two weeks, it can become very complicated if there’s a problem. Noticeably absent from the cosmetic list are sunscreens, which are regulated as drugs, Bellomo says, and must adhere to FDA’s safety standards set for nonprescription, over-the-counter drug products.

About the Author

You May Also Like