In biology, as in business ecosystems, growth is an indicator of health—far preferable to decline. But there is very little in between. In effect, stasis does not exist in business systems. There is an inexorable, organic evolution happening at all times in the marketplace, sometimes punctuated by significant disruption. This disruption—a kind of creative destruction—is quite evident across categories in the food and beverage space bringing considerable distress to incumbent category leaders that are not keeping pace with changing consumer preferences.

While growth is not imperative, managing a declining annuity is largely a financial exercise with relatively little promise for new opportunities, professional development, geographic expansion or other elements likely to appeal to a broad range of ambitious young professionals. It is true that the dramatic cost-cutting that has taken place in the public CPG marketplace was initially rewarded. The momentary brilliance has faded, however, as the reality of low or negative long-term growth has again weighed down stock price and enterprise valuation. It has also accelerated an exodus of senior talent from many of the larger CPG companies.

To understand the economic and business culture dynamics here, we must examine the barriers to innovation and growth and explore a range of strategies and tactics increasingly deployed to meaningfully restore top-line growth—specifically acquisition, corporate venture capital initiatives and participation in business incubators and accelerators.

Innovation as a noun

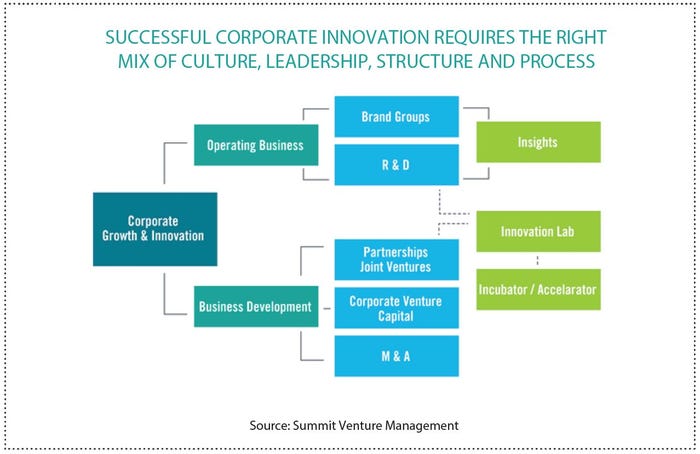

For innovation to prosper in a business ecosystem, there are both hard and soft features that must be in balance—including structure, process, culture, and leadership. Especially for very large companies whose culture and business systems are optimized around successful management of billion-dollar brands (PepsiCo has 22 of these—Nestlé has 30), agility and risk-tolerance are two characteristics that do not fit very well with the finely tuned mechanisms, processes, and incentives needed to power these excellent, highly profitable companies with a vast portfolio of brands.

Many large companies are, in fact, superb at generating and sustaining a steady stream of product innovations. These would typically utilize the existing supply chain, manufacturing resources, routes to market, etc., and be geared to existing core customers and existing consumer demand. And these innovations typically fulfill one of the most difficult challenges—namely, maintaining the terrifically high margins that a large and highly optimized product line can enjoy. That is the good news.

The bad news for these large companies is the collective share loss that the incumbent market leaders have suffered over the past decade to more disruptive innovation. These losses can be attributed to a complex set of changes that add up to a fundamental shift in consumer preferences that are difficult for the incumbent leaders to respond to in a timely and margin accretive fashion. Be they evolving health attributes, ingredient preferences, local or verifiable sourcing strategies, environmental footprint, shifting sales channels, or overall brand and business purpose—the larger and more optimized a product or brand might be, the larger the economic and logistical challenges associated with keeping pace with evolving consumer preferences. Indeed, many legacy brands are built around fundamentally obsolete insights about consumer preference and behavior. Removing the artificial coloring or additives may be a step in the right direction, but such steps will not, generally speaking, restore relevance to a brand.

Experimentation, risk, and agility

In many ways, there are at least two different operating paradigms in the food and beverage business today. And while they operate according to very different playbooks, at the end of the day, they ultimately compete and merge in the marketplace:

The large and mostly public CPG companies operating at low/no growth with high margins defending diminishing market share.

The small and mostly private companies—often with venture capital or private equity backing—operating at high growth rates, generally with compressed margins, doing the disrupting and taking market share.

An important nexus of cultural difference is around experimentation, risk, and agility—and what lurks beneath the surface of this nexus, namely the tolerance for and definition of failure. Failure is generally career-limiting in the world of large-cap CPG companies, and thus, risk is very much to be avoided. Risk mitigation generally translates into hierarchical bureaucracies proceeding at a very deliberate (slow) pace. This is not a lack of good ideas but rather executional risk avoidance and slow time-to-market.

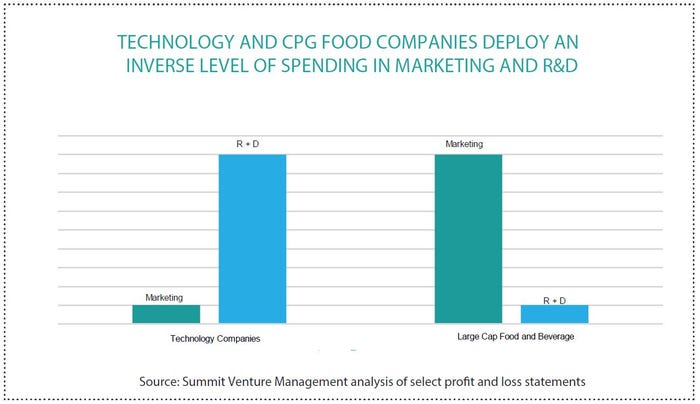

This is where the spirit of Silicon Valley and the tech world has intersected with the entrepreneurial food and beverage world. In place of humiliating, abject, dead-end failure, this entrepreneurial world holds much more tolerance for failure as an opportunity to reframe or pivot or otherwise intelligently and productively fail. “Moving fast and failing forward,” as the saying goes.

Corporate innovation centers—whether captive to one company or shared across non-competitive companies—reflects another approach to stimulating a trial and error, test and learn environment favorable for innovation. Under these circumstances, failure is part of the brief.

So, to a considerable extent, the dynamic that has emerged is a gradual acceptance of, on one side, the rapid pace of change in consumer preference, and on the other side, what needs to be done to get past the barriers to disruptive innovation in large companies. This has increasingly involved the adoption of an outsourced model—including autonomous innovation centers, corporate venture capital, incubators and accelerators—hopefully all to help protect the entrepreneurial spirit from more massive scale bureaucracy.

Corporate Venture Capital

Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) is not at all new to large corporations, though it is relatively recent in the CPG world. An early, celebrated example is the well-established (and already centenarian at the time) DuPont Corporation buying, in 1914, what would become a very valuable stake in the then nascent General Motors Corporation. A dedicated investment fund within the corporation can be a good vehicle to detect and invest in new, potentially disruptive products and companies as well companies that could well benefit for the parent company core competencies.

Large U.S. conglomerates embraced corporate venture capital in the ‘60s and ‘70s, but it was technology companies that later led the way. This was, at least in part, out of the recognition that the pace of technological change was increasing.

The bursting of the tech bubble, beginning in the year 2000, triggered a retrenchment in CVC activity, as companies were required to mark-to-market the deflated value of those investments. (Cisco itself lost 86 percent of its value). But today, 75 of the Fortune 100 corporations have some form of CVC enterprise. And by now, virtually every major CPG company has adopted some form of a CVC fund—at minimum to have a view of where the disruption is coming from.

Unilever, the only CPG company among the 25 largest CVC players, was an early and very active participant. It has invested in and acquired many direct-to-consumer businesses in personal care, household products, and the beauty space, with a bias toward technology-enabled brands. (Dollar Shave Club and Seventh Generation are two such acquisitions). General Mills 301 Inc. is the only food company in the top 75 CVCs—and while it has been the most active fund, many of the bets are small. 301’s ability to influence topline company results remains to be seen, but the cultural impact—the interchange between the entrepreneurs and General Mills’ personnel and infrastructure—may be just as important in the long-run. The group has taken steps to ensure it does not extinguish the entrepreneurial spirit it invested in, and it has demonstrated the intent to learn from its investment partners and acquired companies. Previous bolt-on acquisitions in the industry more resembled a zoo than a natural habitat—with mortality and birth rates suffering.

Tyson Foods, the largest U.S. animal protein company, is an interesting example of a company anticipating disruption of its core business. The company has made investments in both Beyond Meat and Memphis Meats—a plant-based meat substitute brand and a cultured meat brand, respectively. CEO Tom Hays says that the investments are part of a forward-looking effort to meet future consumer demand in a sustainable manner.

Miller Coors, suffering from a decline in mainstream beer, has acquired craft brands and has invested in kombucha and chai companies; and the diversified Constellation Brands (beer, wine, spirits) has just announced a $4B investment in a Canadian cannabis company to ensure it has its fair share-of-buzz across the spectrum.

The currently white-hot investment ecosystem in food and beverage has been fueled by some very rich acquisition multiples, numerous recently formed food-focused venture and private equity firms, and the tremendous competition to fund innovative, high-growth brands. The ample liquidity in the marketplace has also been augmented with a newer and rapidly evolving range of incubator and accelerator models that also provide technical resources and mentoring. This segment of the market is also borrowing heavily from the technology playbook. And as such, we’re likely to see a big batch of FOMO (fear of missing out) investment, well known in tech, and already seen in food and beverage. The latter stages of the meal kit expansion, for instance, saw very good money sacrificed in FOMO frenzy.

Incubators and Accelerators

Business incubators, in some form, have been around for over 50 years in the U.S., often serving in a sector-specific or geography-specific economic development function. Privately funded and venture-based models have also proliferated. In the past decade, Rocket Space spawned Uber and Spotify while Y Combinator spawned Airbnb—attracting tremendous celebrity and inviting much imitation.

While the terms are often used interchangeably and variably, incubators typically include a physical co-working space, technical support and resources, as well as programming and mentoring. The programs might or might not be time limited. As one venture-based example, Y Combinator invests $120,000 in its accepted companies with a 3-month residential bootcamp—in exchange for 7 percent of the company equity.

Accelerators operate in a similar manner. They are typically time bound and involve a cohort class of similar stage companies. Less immersive than a residential incubator, they tend to be structured with regular classroom work as well as one-on-one mentoring.

Many hybrid models exist with an increasing number of food and beverage focused programs—often with commercial kitchen and technical resources available. Some are simple fee-for-service nonprofits such as The Hatchery in Chicago, which serves as an economic development engine with both public and private funding.

Kraft Heinz Springboard program is a new entrant in the field, featuring company-sponsored investment dollars, technical expertise and access to test kitchen space. Chobani sponsors an accelerator program involving a financial grant, programming at its New York office (one week per month for four months), access to its functional experts, as well as ongoing support both from others in the cohort class and relationships forged within Chobani.

Another accelerator, AccelFoods, has morphed from a pure-play accelerator into a venture fund—having accepted investments from Danone Manifesto Ventures and Acre Venture Partners (funded by Campbell’s).

The Techstars accelerator platform, originally technology focused, has essentially franchised and syndicated its model broadly around the world, often with corporate sponsorship and in multiple verticals. It features both membership-based accelerator programs and more recently a $250M+ venture fund for scaling the most promising companies.

While highly fragmented with many different operating models and business models (a preliminary taxonomy is offered in the chart below), initiatives to incubate and accelerate new business ventures are proliferating in the food and beverage space in service of spawning the challenger brands that will write the next chapter in the history of food innovation.

John Grubb is a veteran growth strategy consultant and branding expert focused on food, beverage and nutritional products.

This article originally appeared in the Finance Issue of Nutrition Business Journal. Email Cindy Van Schouwen, [email protected], to learn more about the report.

This article originally appeared in the Finance Issue of Nutrition Business Journal. Email Cindy Van Schouwen, [email protected], to learn more about the report.

Read more about:

InnovationAbout the Author

You May Also Like