This article originally appeared in the Nutrition Business Journal's Awards Issue.

Walking past the protein tubs in the supplement section, few shoppers are likely looking for a callout like “wild-foraged by hand,” but Surthrival co-founder Daniel Vitalis thinks consumers might start looking for it, or at least appreciating it, when they hear the story behind his company’s black walnut protein powder.

As the name makes clear, the powder is made from black walnuts, but what might not be clear to most American consumers is where black walnuts come from, or even what they are. Wild, rarely cultivated and very different from the common English walnut, but far higher in protein, the black walnuts powdered in Surthrival’s pouches are gathered from native trees by legions of foragers and brought to a network of collection stations set up in feed stores and parking lots in small towns across the Midwest, primarily Missouri. The forager might be someone who gathers scrap metal the rest of the year and turns to black walnuts when the days start getting shorter. The forager might be a Mennonite walking the forest with her family in the early autumn. The forager might be a 10-year-old saving money for a new catcher’s mitt.

It’s a very different supply chain story from anything else in the protein powder market, and Vitalis believes that difference will be important to consumers who recognize that “wild-harvested” means nothing gets planted or fertilized or doused with herbicides or pesticides. It means the trees are watered by rainfall. It means forests stay forests. It also means workers aren’t exploited in the harvest.

“This is truly one of those unicorn projects where you’re like, ‘Wow, this is kind of as good as it gets from a supply chain issue,’" says Vitalis, who has become a leader in the wild-foraging movement as a podcaster and host of “WildFed” on Outdoor Channel.

For Vitalis, the story of black walnuts is emblematic of how civilization’s relationship with food has changed. Putting black walnuts into a protein powder provides a very modern and unexpected way to reconnect consumers with long-lost aspects of that relationship.

Black walnuts grow across the eastern half of the United States and are likely regarded by most as a seasonal task akin to weeding or cleaning the gutters, rather than a source of clean protein. Very different from the English walnut, black walnuts fall to earth as thick husked globs filled with an inky ooze. Not only are the walnuts a poor fit for the American vision of a pastoral backyard—“You’ve got these rotting black tennis balls in the hundreds up among the trees in your yard,” says Vitalis—making use of the nuts is no small task, a lot of work for a small amount of edible ingredient. Native Americans turned to them for food, and Anglo settlers would view them as a backup nutrition source, but as food became industrialized and expectations changed, black walnuts retreated to niche uses in candies, baked goods and ice creams.

“They went from being this great backup food source to being a real nuisance for people,” Vitalis explains. “They got relegated basically to this little category of baked good and grandma making cookies and cakes with it at Christmas, but otherwise barely represented in the food supply.”

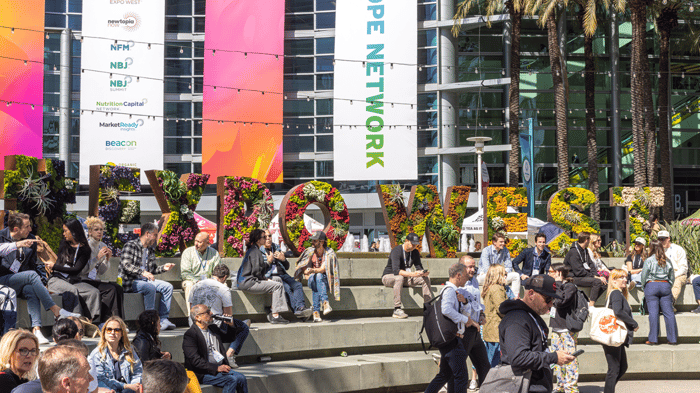

For its sustainability efforts and more, Surthrival won an Expo East 2023 NEXTY Award for Best New Planet-Forward Product.

Buckets and baskets

Jacob Basecke’s family has been keeping black walnuts in the food supply for nearly 80 years and now provides the raw ingredient for Surthrival’s protein. The only surviving black walnut company of its kind, the Missouri-based Hammons Products Company built the network of collection stations and deploys the hulling equipment to process the nuts in all those midwestern parking lots. It’s Hammons that pays the foragers who are wading into the forests with buckets and baskets.

Basecke is well aware how retro that all sounds. “It’s kind of part of our upbringing, part of our culture here, but, yeah, whenever I talk to people outside of the Midwest and tell them how black walnuts are sourced and the vast network that we have and all the people involved, they’re blown away,” says the Hammons executive vice president, whose great-grandfather founded the company in 1946. He describes an “all walks of life” army of foragers. “People do it for the money. People do it for the sustainability, to clean up their land. They will do it as a family activity, kind of a tradition. They bring out their kids or their grandkids during the fall weekend, when the weather’s nice.”

The “vast network” Basecke describes shrinks and grows across the years, depending on the harvest and how many find the time and the interest in foraging. During the great recession, “We had very, very strong crops,” he says. But the system is largely the same as it ever was—hulling stations in parking lots and people in the woods gathering walnuts. What’s new, Basecke explains, is opportunities like Surthrival.

There is a whole universe beyond the baking and confection space to which black walnuts have been traditionally consigned, Basecke believes. Black walnuts have the highest protein of any tree nut, he says, and they are low in saturated fat and deliver minerals, fiber, vitamin A and iron. “They’re rich in polyphenols and have anti-inflammatory properties. So, they have all these really critical health-promoting benefits.”

Basecke describes a “huge uptick” in interest in those health benefits, but the protein powder and the connection with Vitalis and Surthrival happened almost by chance. The company had a byproduct from making black walnut oil that they thought had potential as an almond flour-like product, and Vitalis had reached out to interview somebody at the company about the foraging aspects for his show. It was a “perfect fit,” Basecke says.

Vitalis and Hammons partnered on developing the powder—CO2 extraction was key, Vitalis says—and Surthrival is in the business of getting it noticed, bringing black walnut back into the food supply in a new way.

“We’re going to stay in our lane over here, which is we focus on black walnuts,” Basecke says. “This guy [Vitalis] is passionate about wild foods.”

Foraging abundance

Beyond making use of a biomass quietly rotting on the ground across a giant swath of the American landscape, Vitalis also believes there is a value in people connecting to the foraging idea, whether or not they have any intention of doing it themselves. The modern American forager is a very different kind of forager, and Vitalis knows the people who follow his show and postings are out there gathering food for the experience, rather than the calories, he says. “It just gives people a sense of connecting into something bigger. So, today’s foraging culture is mostly people who forage at hobby level because of how it feels for them to do it, not because they need to do it,” he explains.

That foraging has been labeled elitist when it was once how the truly desperate fed themselves may qualify as ironic, Vitalis says. “Now, we’re at this funny place where I’ll get accused of privilege for getting to forage,” he says. Buying pricey protein in a bag off a shelf may also hint at privilege and certainly strains the connection to “foraged,” but Vitalis contends that consumers will still appreciate knowing their protein powder comes from wild woods and is gathered via this seemingly old-fashioned system.

The appeal, he says, is multifaceted. The labor issue stands out. “The labor force is these volunteers, and so you don’t have suppressive or unfair labor practices,” Vitalis explains. And labor is just the start. “If your thing is ‘Buy American,’ you don’t get a more American story than an endemic tree that’s on our landscape now.” After that might come the environment. Only a fraction of the nuts Hammons processes come from orchards. The rest come from trees that grow wild and require no watering, fertilizer or pesticides. “They are part of an intact landscape,” Vitalis explains.

Every part of the nut is also put to use. The shells go into polishing compounds. The husks are used in anti-parasitic formulas. “So not only are the trees being kept on the landscape, but you also are using all the parts of the nut. So that’s also really a kind of beautiful, complete story there,” Vitalis says.

Because they are wild-foraged, an organic seal is not possible, but Vitalis says the protein powder passes tests for glyphosate and other contaminants. The labor and environmental issues won’t matter just to consumers either, Vitalis says. “We’re heading into a world where these kinds of ethical issues around sourcing are not just going to matter to people emotionally, but we’re heading into that ESG era where it’s going to matter, actually, at a financial level.”

On the shelf

Again, “wild-foraged” is not something the average consumer is likely to expect to see on a pouch of protein powder, but Malcom Saunders isn’t expecting the average consumer to respond to it. The Canadian herbalist founded Light Cellar Super Foods in Calgary, which he describes as a “more boutique” health food store for people who are looking for “that little bit of edge.”

Surthrival’s black walnut powder has plenty of edge, Saunders says, more than enough edge to draw in people who want to move past the more commoditized plant protein powders like pea and rice. Surthrival’s protein is for “a more discerning customer looking for a better story.”

“The idea of wild, North American sourced appealed to people. So, it’s just kind of that slight edge. It’s like, ‘Wow, this is new. This is interesting,’” Saunders says.

That’s certainly what Vitalis wants to hear. A protein powder is very new to Surthrival’s lineup, which had focused on narrow-niche specialty ingredients like pine pollen and elk antler, but Vitalis says the backstory is something that could put the company on the map in a whole new way. “A big part of this project is how do we make this a relevant food because it’s endemic. It’s abundant—it’s got a beautiful sourcing story,” Vitalis says. “It’s clean and it’s extremely high in protein.”

Hammons might not be ready to scale up tomorrow. Basecke says the company is working on how to recruit younger foragers as the population going into the woods with those baskets ages. But he also knows how much protein is out there, lying on the ground, waiting for brands like Surthrival to put it to use.

Hammons processes 25 million pounds of black walnut in a good year. It’s just a start, Basecke says. “You say 20 [million] or 25 million pounds, and it seems maybe like a lot to some people, but there are hundreds of billions of pounds that are not being collected.”

The NBJ 2024 Awards issue is available at no cost at the NBJ store. Subscribe today to the Nutrition Business Journal.

Read more about:

SustainabilityAbout the Author

You May Also Like