The Future of Food: Preserving biodiversity, navigating climate change

By creating an economic reason not to cut down the trees in southern Ethiopia, KAIBAE's founders help communities adjust to their new agricultural reality.

New Hope Network encourages its community members to share open and transparent dialogue about issues that are impacting the food industry and its future. Please help us keep this conversation going. If you’re interested in sharing your opinions on the future of food, email Jessica Rubino at [email protected]. All opinions are welcome.

Consecutive years of below-average rainfall in the Horn of Africa have created one of the worst climate-related emergencies of the past 40 years, forcing millions of families to leave their homes in search of food and water. The unprecedented impacts of multiple failed rainy seasons have created a humanitarian crisis in a region already impacted by cumulative shocks including conflict and insecurity, extreme weather conditions, climate change, high food and fuel prices, desert locusts and the extreme socio-economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. Reliance on the natural resource base in the region—trees, shrubs and grasses—has never been greater, even as those same resources are being stretched to max capacity.

During the dry season and the tail end of a drought, much of the land in this area of southern Ethiopia is desiccated and seemingly barren. The soil itself has become hydrophobic, its wind-swept brittle crust effectively sealed against rainwater absorbing in any appreciable or productive way. Through it all, with no new grass for animals to feed upon or any ability to coax crops from the ground, people are more reliant on trees than ever before.

In more stable times, trees provide welcome support for pastoral and agropastoral communities whose patterns are intricately tied to the land. Primary crops of sorghum or millet complement the milk, blood and occasional meat of their animals. Camels and cows are longer-term investments; goats and sheep are the more fungible currency able to be sold at a moment's notice to cover any number of more immediate household needs: food, medical care, transport, celebrations, and ceremonies. Transhumance—the seasonal movement of animals and people in search of water and pasture—is the dominant pattern in this dry region, though generations have practiced mixed cultivation of drought-tolerant crops together with animals. These systems are predicated on a land base able to support such movement and crop growth, though the poor rainfall has stretched these processes in ways not seen for generations.

Trees have always been important in these areas. Some of history's most iconic and mythical species find ancestral homes here: frankincense (Boswellia sp.), myrrh (Commiphora myrrha) and baobab (Adansonia digitata)—trees mentioned and celebrated in both the Bible and the Quran. While acknowledged historically, countless tree species continue to provide a biodiverse range of important products. Fodder for animals, fibers from the bark, native fruits, fuel, building materials, medicines, flavorings, dyes and resins—these are described as non-timber forest products, as their benefits are appreciated without cutting the trees down. In times of stability, trees are not cleared at unsustainable levels. In times of crisis, such as the current drought, trees become even more important, though also more threatened as hunger and poverty lead to more intensified deforestation. Burning charcoal and cutting wood for fuel are some of the most ecologically destructive yet quick cash-generating opportunities available.

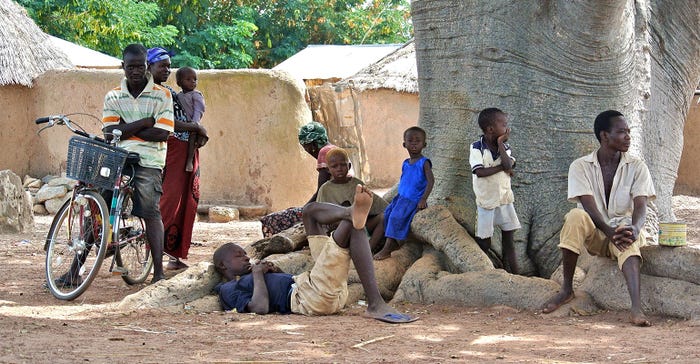

Sustainably managed, the biodiversity of living trees and their range of products and ecosystem services prove to be far more valuable than trees that have been cut down. Through KAIBAE, we have seen this clearly with the baobab supply chain in Northern Ghana, where the annual harvest of baobab pods and leaves has become the most important source of income in many communities. Instead of cutting the baobabs to clear more land for farming millet, farmers working with KAIBAE recognize the value and utility of conserving these important trees throughout the landscape.

A recent trip to the Konso region of southern Ethiopia demonstrated just how important trees can be, especially for communities reeling from the drought. I first visited a Konso farmer more than 30 years ago, and that experience led me directly to a lifetime of working with plants and food. The Konso are famous for the conservation-minded elaborate terracing of their steep rocky soils. They are also well known for integrating native Moringa and Combretum trees into their cropping system, a form of agroforestry that has proven incredibly practical and prescient in the present drought.

As the irregular rainfall and uncertainty of rain-fed cultivation increases in those communities on the front line of climate change, it will be the deep-rooted, well-established trees that continue to provide income and food. The conservation and promotion of such tree systems in fragile landscapes help achieve what I call perennial stability. For those farmers whose lives and livelihoods derive from managing their environment, it will be the stability afforded by trees that will allow them to successfully mitigate and adapt to climate change.

Thomas Cole is a humanitarian aid worker, botanist and the field-focused face of KAIBAE, who often works with communities living on the front lines of climate change.

About the Author

You May Also Like