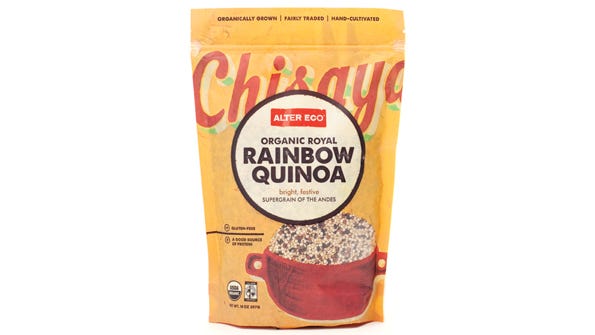

Breaking down Alter Eco's quest for sustainable packagingBreaking down Alter Eco's quest for sustainable packaging

Sourcing and developing the coveted pouch package that doesn’t have to go straight to the landfill was no easy task. Alter Eco Supply Chain Director Jeanne Cloutier shares the company's story.

Many brands spend months, maybe even years, developing an amazing, carefully sourced organic, fair trade product with quality ingredients that consumers will love. And then they package it in a piece of trash.

Alter Eco is one of the companies addressing that dissonance by attempting to make all of its packaging as sustainable as possible and using compostable wrappers for its truffles and, more recently, its stand-up quinoa pouches. But sourcing and developing the coveted pouch package that doesn’t have to go straight to the landfill was no easy task. Here, Jeanne Cloutier, who is the company’s director of supply chain and also works with the compostable packaging coalition OSC2, talks about the process and the company's motivation. (Scroll down for a video to see how it works.)

You have two distinct products with compostable packaging. Was it the same development process for both?

Jeanne Cloutier: The truffle wrappers have been on the market for three years; they are a different supply chain stream. We worked with our chocolatier in Switzerland to source those wrappers. The  packaging printer used a monolayer of NatureFlex, which is certified compostable, and also certified compostable ink. That was the first time they’d ever done that at that printing facility. The pouches were in development for much longer—about five years. The truffle wrappers were easier because they were only one layer.

packaging printer used a monolayer of NatureFlex, which is certified compostable, and also certified compostable ink. That was the first time they’d ever done that at that printing facility. The pouches were in development for much longer—about five years. The truffle wrappers were easier because they were only one layer.

What were some of the biggest challenges you encountered in piecing together this compostable pouch?

JC: We are very sustainability focused, and we push the envelope in terms of what we can accomplish. We wanted a package that was plant-based, compostable instead of recyclable—because we don’t think consumers actually recycle flexible plastic—and the materials had to be non-GMO. So once all of those were sourced, we had to make sure that they functioned together and would laminate together. We had to make sure that the side seal and the bottom seal would hold weight, because we’re packaging quinoa. And that it would survive distribution and handling tests and going on manufacturer’s filling machines the same way that a conventional polyethylene pouch would.

There was a worldwide search for suppliers of compostable ink, compostable print layer and compostable sealant layer. Only one of them was based in the U.S., so the materials had to come in from elsewhere. We also had to make sure that the materials were indeed certified, because there’s a lot of stuff kind of in R&D or anecdotally compostable, but we had to make sure all of our suppliers were certified or in the process of being certified.

The important thing to note about calling something 'compostable' is that it’s different from the word 'biodegradable,' which means it breaks down. The material has to be usable; it has to turn into a part of usable soil.

It’s interesting that you mentioned that you don’t think consumers would recycle a pouch. What makes you think they’ll actually compost it?

JC: When this process all started five years ago, we had just transitioned from bag-in-a-box type of package, kind of like a cereal, to a regular polyethylene standup pouch, because we wanted to reduce our packaging. But the response from our consumers was that we appeared to be actually less sustainability-minded by doing that, because it was just plastic. The perception was that it was worse. We were shocked!

We dug into that supply chain and realized that every single pouch on the shelf is not able to be recycled because it’s made from two different laminated plastics, and you’d have to pull them apart, which you can’t do. So we were putting this ethical, organic, fair trade, carbon-neutral, everything product into a piece of trash. So we said, 'OK, what are our options?' We explored using a recyclable flexible plastic, but the only way to recycle that—you can’t put it in your blue bin, otherwise that would be a slam dunk—is to take that bag back to the store to a particular recycle bin (what you put plastic shopping bags in) and then they would be collected and taken to a specific resource recovery plant that can deal with that kind of plastic. We thought, who’s going to do that? So then we thought, let’s do something that just disappears and goes away.

Nothing is perfect. We don’t think most people are going to compost it. We think some people will compost it at home; we think people with municipal pickup, such as in San Francisco and Seattle where you can put compostable into your green bin, will do that; and there’s a lot of areas of the country where people are going to put it in the landfill bin because the municipal collection system doesn’t give them a choice. So the question is, what level do you design to? Do you design to the lowest common denominator and keep making trash? It’s really an encouragement to the municipal waste systems to provide more opportunities to recover this resource.

About the Author

You May Also Like